The Heartland of Hellenism: The Greeks in Illinois 1886-1924

From Working to Preserve Our Heritage: The Incredible Legacy of Greek-American Community Services

"Below are the panel labels related to the Heartland of Hellenism exhibit that Steve Frangos provided from his collection. We do not know if this is the final version or an earlier draft. We were not able to locate any of the exhibit’s photos, Steve had captions for some of the pictures that were part of the exhibit, and I have included them here. Although this was part of the larger O Cosmos exhibition, we do not have any labels beyond Heartland. At least four panels with several pictures and labels on each panel are missing. Given the nature of the content, and that the exhibit is no longer around, I have included what we do have as a means of preserving this history to the extent possible.

Introduction The following museum labels are those of the exhibition entitled: “The Heartland of Hellenism: The Greeks in Illinois 1886-1924.” This independent exhibition discusses the lives of individual Greek Americans as they exemplify generally accepted historical events known to have occurred for the community at large. The Heartland exhibition is scheduled to appear at various locations in the downtown area of Chicago, Illinois.

Panel 1: Pioneers Sailing up the Mississippi and Chicago rivers, Greek travelers first came to Illinois in the early 1840s. As ordinary traders and ship captains, these pioneers were just a few scattered figures in the bustling crowds even then found along the Illinois river towns and in the growing port traffic around Fort Dearborn. One of these early Greek pioneers was Captain Nicholas Peppas who eventually returned in 1857 to settle permanently in Chicago. Captain Peppas lived on Kinzie Street for more than fifty years and lived to see the massive waves of Greek immigrants arrive in the 1870s and 1880s and form their own community around him. A close friend of Captain Nick was Frank Brown, whose name in Greek was Fotis Kotakis, a barber for many years in Chicago who came from the Greek island of Samos in 1859. Another of the first pioneers was Constantine Mitchell (Michalopoulos), a captured Confederate soldier. Mitchell was held prisoner by the Union Army in Chicago and after the Civil War decided to settle permanently in Illinois. In the midst of the Civil War, another Greek “Uncle” (or in Greek Barba) Thomas Combiths, a tailor, moved to Chicago. In 1869, his son Frank Combiths was the first child born of a Greek immigrant father in Illinois. Frank Combith’s mother was not of Greek descent and there were no Greek women in the entire Midwest for many years.

The First Family In 1885 the first Greek couple established their home in Illinois. Peter Pooley (Panayotis Poulis), a ship captain much impressed by the development in Illinois, returned to his native island of Corfu, Greece, and married Georgia Bitzi. By 1886, Georgia Bitzi Pooley, a well-educated and dynamic woman, organized the Greco-Slavic Brotherhood for the purpose of founding a common house of worship.

Panel 2:Tsakonas and the Tsintzinians

Christos Tsakonas (1848-1909) called the ‘Columbus of the Spartans’ arrived in Chicago in 1872 soon after the Chicago Fire. Christos Tsakonas was born in Tsintzina, a secluded mountain village in the very heart of the Parnon mountain range northeast of Sparta. Tsakonas is a singular figure in the history of Greeks in Illinois. It was through the offices of Christos Tsakonas that directly or indirectly over 1,000 young Spartans arrived in Illinois during the late 1870s and early 1880s. Furthermore, these first massive waves of Greek immigrants to Illinois were almost exclusively from the village of Tsintzina.

United States Immigration forms were not prepared for the rural Greek perspective of being from the single village of Tsintzina when they wrote down as ‘village of origin’ the names of two villages in the Evrotas valley: Goritsa and Zoupena.

Residency patterns that are a consequence of the transhumant lifestyle in the mountainous parts of the Greek mainland result in double or multiple houses all owned by the same family. During the movement of flocks in the summer the family moves to the high mountain pastures and to the house and work buildings used during this season of the year. In the winter months, the flocks and their shepherds move to the lower winter villages. This practice of multiple residences is called diplokatoikia. Tsintzina, situated as it is high up in the Parnon mountains, was even in Christos Tsakonas’ time, principally occupied only during the summer months. Goritsa and Zoupena down in the Evrotas Valley were winter villages.

The U.S. immigration forms precluded any of the social conditions and seasonal residency patterns traditional to a transhumant way of life. Consequently, the chain migration of the Tsintzians into Illinois in the 1870s and 1880s was only recently recognized by Greek-American historians.

The historical contributions of Christos Tsakonas and his fellow Tsintzinians in Illinois are profound. Therapnon, the first Greek society in Chicago, was composed principally of Tsinztzinians. Other Greeks mentioned in the membership rosters when not from Tsintzina were from the same region where this village is located, Arcadia. These Greek immigrants were most notably from the villages of Vasaras, Krysapha, Agriannos, Geraki, Arachova, and Vamvachou. In 1891, it was the Therapnon that provided the leadership necessary for the establishment of Illinois’ first Greek Orthodox church, Holy Trinity.

Tsakonas and his Tsintzinians also offered a powerful example of cooperative business management not lost upon the subsequent waves of Greek immigrants to Illinois. Through complex and wide-ranging business networks the Tsintzinians began a string of wholesale fruit and candy stores that eventually extended down from Milwaukee, across Chicago, and continued through Ohio into western Pennsylvania.

Up to that time, in no other line of business were Greeks better established or more recognizable to the general American public than the confectionery trade. By the 1920s, there were more than 300 Greek-owned candy and ice cream parlors in Chicago alone.

Panel 3: The Return of Odysseus The mid to late 1890s were a difficult period for Greek immigrants in Illinois. In 1893 at the Columbian World Exposition, the Streets of Constantinople diorama presented Greeks as mere street vendors in the Ottoman Empire. National newspaper publicity had reported the controversies over the belly dancing at the Chicago Fair and many Americans associated the new immigrants from southeast Europe, the Greeks included, with this scandalous oriental dancing. These events and the negative responses they daily engendered grated on the pride of the Greek immigrants. In 1897, the year of the brief Greco-Turkish War, Greeks demonstrated in a large rally and parade on Clark Street that frankly upset the majority of Chicagoans. ‘Where do the loyalties of the Greek immigrants lie,’ writers of the day asked, ‘with America or their country of origin?’

An unexpected problem from the Greek immigrant’s perspective was that the average citizen in Illinois did not know anything about Greece let alone its classical heritage. Many accounts from the 1890s and early 1900s exist of the Greek immigrants striving to educate the American public about the glories of Classical Greece. The Greeks quickly concluded to use their cultural heritage for political ends. Across the nation there soon developed, in virtually every Greek community, sustained efforts to educate the wider American society not only about Ancient Greece but how the foreigner selling fruit, produce, and penny candy was the direct descendant of this celebrated people. In Illinois, this agenda found expression on December 7, 1899, when the Greek immigrants presented the classical Greek tragedy, The Return of Odysseus at the Hull House Theater. Not only was this the first dramatic production at the Hull House Theater, but the play was also a resounding success. The Return of Odysseus received such favorable reviews it proved to be the first unreservedly positively publicly held event by the Greek immigrants of Chicago.

Lorado Taft, a member of the audience on the opening night, made these observations in the Daily Record on December 13th. ‘The thought which came over and over again in every mind was: These are the real sons of Hellas chanting songs of their ancestors, enacting the lives of thousands of years ago. There is a background for you! How noble it made these fruit merchants for the nonce; what distinction it gave them! They seemed to feel that they had come into their own. They were set right at last in our eyes…The sons of Princes, they had known their heritage all the time; it was our ignorance which had belittled them. And they waited.The feeling which these humble proud fellow citizens of ours put into the play was at the same time their tribute to a noble ancestry and a plea for respect. Those who saw them on that stage will never think of them again in quite the same way as before…’

Panel 4: The Families of Men

Before 1930, the vast majority of Greek “families” in Illinois, as in the rest of America, were groupings of male relatives. Fathers and sons, groups of brothers, cousins, men joined by spiritual kinship (koumbaroi), and even men from the same village or district in Greece, formed communal households throughout Illinois. Jokes and long-involved stories are still told of these all-male households.

Undoubtedly the rapid rise of Greeks in a number of businesses was due to the strict economy of their communal lifestyle. In Illinois, Greek immigrants soon dominated a whole range of businesses such as fruit and vegetable stores, candy and ice cream parlors, vaudeville houses and movie theaters, shoe-shine parlors, and eventually restaurants. Tight kinship networks in Illinois dovetailed into the new business networks across the state. Brothers who individually owned a number of stores would buy collectively from wholesalers and so underprice their competitors.

The extent of the collective efforts of rural Greek businessmen has long been overlooked. One example would be the many groups or confederations of Greeks in the grocery store business who regularly and collectively purchased huge shipments of canned goods and produce.

As representatives of these all-male family groups, we can cite the experiences of the four Rapanos brothers. The Rapanos family came from the remote mountain village of Planetarou in the Kalavryta region of the northern Peloponnesus. In 1905, Nickolaos Rapanos sold his entire flock of three hundred goats to pay the passage money to America for his oldest son, thirteen-year-old Athanasios. For the next fifteen years, by pooling money Athanasios sent from Illinois with whatever he could raise in the village, Nickolaos would travel back and forth from Planetarou to Chicago. During each one of these extended trips to America, he brought another son to work with Athanasios.

By 1918, Nickolaos and all four of his sons were selling fruits and vegetables from horse-drawn wagons. Sometime between 1920 and 1921, the family had both a storefront grocery store and two teams of wagons. This particular family was no different than many others in Illinois during this era. All five men lived in a two-room apartment on Dewey Street with their horses stabled nearby.

With twelve-hour workdays and five sisters to dower back in the village, tensions ran high. Fistfights were far from infrequent. Soon every one of the brothers had a store. The four brothers purchased their fruit and produce collectively for many years. Whatever disagreements they had privately, in public, as far as the American consumer could see, they each appeared to be no more than another smiling Greek selling produce.

Panel 5: 1917-1918 Liberty War Bond Rally

Few Greek Americans of the post-war generations are aware that the pioneer Greek immigrants were among America’s most despised minorities. Newspapers across America carried stories of the newly arriving Greeks as scabs and strikebreakers who frequently resorted to violence as a means to settle public and private disputes. Greeks quickly sought ways to alter the American public’s perspectives of their actions.

Here we see the 1918-1919 Liberty War Bond Drive Rally sponsored by the Greeks of Chicago. Rallies such as this one were a mixture of sincere appreciation for all that the Greek immigrants had gained in America along with a desire to have their accomplishments and the value of their traditional culture recognized.

To be ‘foreign’ does not mean an individual simply speaks another language. The differences in basic beliefs and values are what separate one group from another. The Greek perception that if you are aligned with a powerful group you share in their collective prestige is diametrically opposed to American values and sensibilities. From the American perspective, an individual is to be judged by their personal accomplishments and character.

Greeks were truly perplexed when the Americans did not alter their daily interactions with them after all the much-publicized rallies and parades. It was many years before the Greeks came to recognize that the pride they felt in their discussions of Ancient Greece while weighing bananas for their customers, would be so misunderstood. The public rallies and the elaborate interiors of grocery stores, shoe-shine parlors, and candy stores, along with all the talk of Socrates and Aristotle, were more than irksome to many Americans, it was often laughable.

Panel 6: Death Photographs

The majority of Greeks who came to America in the 1890 to 1924 era envisioned their journey to be of only a short duration. The intention expressed was to work in America just long enough to pay for a sister’s dowry or earn enough money for a grove of olive trees and then return home to their village. Out-migration for seasonal or temporary work abroad was then, as now, a centuries-old tradition for Greeks. The ksenithia, literally the foreign lands, is so much a part of the Greek historical experience that it permeates all aspects of the culture and society. In hard economic terms, ‘Remittances from Abroad’ have always played a decisive role in the economic development of the modern Greek nation-state.

Much is made of the economic advantages that Greeks found when they arrived in the United States. The consensus of most published accounts attributes the decision by the Greek immigrants to make America their permanent home as a pragmatic response to obviously superior economic conditions. These speculations about ‘objective’ economic motives address none of the emotional realities these young men experienced far from family, home, and country.

In strictly emotional terms, the 1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic which swept throughout the Balkans was especially devastating for many Greeks in Illinois. Entire families, and even whole neighborhoods in the more remote villages, were wiped out by the epidemic. Envelopes edged in black, the traditional sign that the enclosed message spoke of death, streamed into Illinois. With no one to go back to, or at the very least a beloved mother or sister was taken by the plague---some men could simply never go back.

Since 1839, with the introduction of photography in Greece, photographs taken at funerals have served as public documents of these solemn events. Such photographs were often sent to families working abroad. At times of massive catastrophes, such as the 1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic, it was impossible to take such photographs. The sister, mother, and first cousin of one Greek immigrant to Chicago, Zafiri Psychios, are shown in this circa. 1917 photograph taken just outside of the family’s home in the rural mountain village of Vlasia in the Kalavryta region of the Peloponnesus. These people are Olga Psychios, Theodora Psychios, and Theodore Baroutis. Between the 18th and the 24th of November 1918, all three individuals died of the Spanish Flu.

This image eventually served as a death photograph with three crosses in pencil drawn above the figures and the dates of their deaths written in ink at the bottom. A much-treasured document, the original photograph reflects the changing emotional responses of its owner to those three deaths in 1918. As the years went by, the three penciled crosses were erased. And when the pain of a beloved sister’s death was finally accepted, the date of her death was erased as well. Zafiri always associated this photograph with the fact that he grew hollyhocks in his garden in Rogers Park on Chicago’s far north side. Zafiri said it reminded him of the flowers near his family home that his mother and sister always grew.

Panel 7: The Greek Record Company of Chicago, Illinois

In the early 1920s, the very first record company in America owned and operated exclusively by Greek immigrants, The Greek Record

Company began to issue a long and distinguished catalog of traditional Greek music. The founders of this famed record label were the two immigrant musicians George Grachis, a violinist, and Spiro Stamos who played the cymbalon, which is a traditional Greek stringed instrument similar to an American hammer dulcimer.

Sotiri (Sam) Chianis, the noted musicologist (and a recognized master Santouri player in his own right) observes that the Greek Record Company of Chicago ‘…quickly earned a national reputation by featuring prominent folk artists of the era. In addition to Stamos and Grachis, the artists included Amalia (vocal), the singer A. Katsanis (better known by his nickname Mourmouris), Angellos Stamos (vocal), Konstantine Patsios (vocal), Marikia Papagika (vocal), Epaminondas Asimakopoulos (vocal and laouto), Harilaos Papadakis (vocal and Cretan Lyra), and the folk clarinetists Nick Relias and Konstantine Fillis’”

Early in the 1920s Rast Taxim, To Hanoumeko, Helleniki Rapsodia, Kalamatiano Horos, and other enormously popular dance records were recorded by the same compania featuring George Grachis on violin, Spiro Stamos on cymbalon, and Angellos K. Stamos on vocals (c.f. Greek Record Company 513 A/B, Greek Record Company 512 A, and Greek Record Company 514 A).

Panel 8: Greek Muses in America

Introduction

The very moment the young Greek men stepped into Illinois, all the traditional arts of Greek culture and society arrived with these new immigrant laborers. Music, dancing, foodways, icon painting, needlework, wood carving, and a host of other expressive forms were a daily part of the immigrants’ new lives. Fueled by the experience of a new way of life in America, many of the traditional arts saw a unique fusion where the rural folk arts were presented and performed in an original Greek-American fashion. Still, each piece of artwork or performance must be approached cautiously. To the untrained eye, what may at first appear to be influenced by the new life in America, is a traditional Greek way of expression.

Vlasia Remembered

The needlework artistry of men is often forgotten in accounts of Greek fabric art in America. This is especially curious since few Greek women were even in America, let alone Illinois, until the 1920s. This splendid example of Greek-American embroidery was completed in 1915 by Zafiris Y. Psychios. Zafiri was born in the mountain village of Vlasia in the region of Kalavryta in the northern Peloponnesus. Zafira came to the United States of America in 1912 at the age of seventeen.

The incorporation of a photograph with embroidery is a design style that evolved out of rural Greek villages. With the introduction of photography into Greece in early February 1839, the villagers were quick to include these new images into their existing artistic creations. Photographs with surrounding embroidery along with elaborate beadwork can be found throughout Greece and in Greek communities around the world.

In this particular photo-embroidery piece we see Zafiri celebrating his continued identification with his home village. What must be obvious to the attentive viewer is the close compositional similarity between a photo-embroidery such as this one, and two other photograph genres seen in this exhibition: the oval plate photographs and the composite photographs.

Panel 9: Composite Photographs and Family Portraits

Countless Greek immigrants were separated from their families for years. Many men never saw any of their families again. In their years of toil in Illinois, some men could simply never accept that this temporary sojourn to Illinois might last a lifetime. In Greek culture, there is no separation between action and belief. The Greek folk saying most often associated with this strongly held point of view is “How can you know what another [person] is thinking?” What a person does is, in fact, what he or she believes. Intentions separate from action are meaningless.

This straightforward belief saw one form of expression in America with the widespread use of composite photography. A simple procedure for any studio photographer was the juxtaposition of any two photographs that could then be photographed as a single image. These composite photographs, as integrated balanced images, vary according to the original photographs and the skill of the studio photographer involved. Sometimes it is difficult to tell a finely worked composite photograph from a carefully orchestrated studio portrait. At other times the crudity of the collected photographs borders on the comical.

The desire for family, its public display, and the denial that any separation was a permanent condition can be seen in these commonly found composite photographs. Christos Saramantis, one of the original founders of Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Chicago, can be seen in this circa. 1903 composite photograph with members of his family back in Greece.

Panel 10: The Greek Heritage in Rural Illinois

The experiences of Greek immigrants and their families in rural Illinois have yet to see inclusion in the historical accounts of ethnic groups in the state. The history of Greeks in Illinois is presented as an urban experience focusing almost exclusively on Chicago. Demographically the greatest concentration of Greek immigrants to Illinois has settled in Chicago and those towns, suburbs, and villages immediately adjacent to the city. Still unrecorded, except in Greek sources, are the experiences of Greek immigrants in the most rural areas of Illinois.

The most valuable sources for determining the presence of Greek immigrants in rural Illinois are the Greek language business directories, histories, and guidebooks produced since the turn of the century. The original intention of the business directories was to provide a listing of Greek businesses and wholesalers state by state all within one reference source. The success of these directories was immediate.

The idea was simple. If provided a choice, a Greek immigrant would buy from a Greek businessman who in turn would buy from a Greek wholesaler. This scenario, while imperfect in practice, worked well enough for these directories to be produced year after year. The sheer volume of these publications attests to the fact that they received wide attention among Greek immigrants.

Many Greek writers and publishers produced directories, business guides, and even dictionaries that included descriptive sections on cities and states across the United States. Seraphim Canoutos was undoubtedly the most prolific of these business directory compilers, issuing such publications annually from at least 1907 until the late 1920s. Canoutos did not limit himself to business directories but also wrote legal guides, history books, and even a book of manners.

From our perspective on history, the present value of these directories resides in the fact that they document page after page of Greek-owned businesses cited with a street address and type of business for every state in America. In the specific case of Illinois, we can chart the presence of such Greek-owned businesses beginning in 1903. Odigos Tou Laoi, The People’s Guide, written and compiled by C.D. Skadopoulos in 1920, is one of the variations on the business directory format. It is a book of manners in section one and section two is a business directory. What makes the People’s Guide such a valuable historical document is that the majority of businesses cited in the pages are accompanied by photographs of the owners, frequently with a short biography.

Panel 11: The Antioch Café

Not every Greek immigrant living in rural Illinois in the early part Not every Greek immigrant living in rural Illinois in the early part of the century is included in Greek business directories. of the century is included in Greek business directories. One such case of rural Greeks was three families living in Antioch, Illinois in the mid-1920s. In 1924 three Greeks, two cousins, and a friend, from the same village in Greece, opened the first Greek restaurant in Lake County, Illinois. The three young Greeks called their new establishment the Antioch Café. The three co-owners were Dan Harris (Anastacios Haralambopoulos), Sam Harris (Zafiri Haralambopoulos), and Ted Poulos. All three men came from the village of Vlasia in the Kalavryta region in the northern Peloponnesus.

The Antioch Café was an unmitigated economic disaster. One day in the dead of winter in 1925, a lone man came into the Antioch Café at 6:00 a.m. The three Greeks were all a bustle, but the man only wanted a cup of coffee. The entire day passed without another customer. Then just before 6:00 p.m. the same man who had been there for his morning coffee came in and ordered…another cup of coffee.

Sometime in 1925, Sam Harris sold his holdings in the Antioch Café. Sam moved south to Libertyville, Illinois, going into business with another Greek man who is only recalled by his last name, Pasinis. The two men owned a grocery store on the west side of Libertyville’s main street just north of Cook Street.

In 1931 Dan Harris was killed in an automobile accident and his widow sold her share of the Antioch Café to the remaining partner, Ted Poulos. Until sometime in the late 1930s, Ted Poulos owned and operated the Antioch Café. Ted then went into a business that, unlike the Antioch Café, would bring him unexpected fame and recognition throughout the county. In the recently published book Antioch, Illinois A Pictorial History 1892-1992, Ted’s Sweet Shop, the local confectionery store, is commemorated in a two-page spread of pictures.

'Oh, you mean Ted the Candy Man?' is how longtime residents of Antioch, and Lake County in general, refer to Ted Poulos. For nearly forty years, Ted Poulos received acclaim far and wide for his hand-made candies. Ted was often the subject of newspaper stories for his elaborate Easter baskets made of hand-spun candy or the six-foot candy canes he gave to the local Boy Scout troop every year.

Descendants of all three men still live in Lake County, Illinois. With the phenomenal new growth in this quickly developing county, many people make it a point of stressing how long their families have lived in the area. Just the mention of Ted’s Sweet Shop, or even the Antioch Café, and local people smile. The memories of these Greek immigrants live on in the stories their neighbors still recall. As one person prefaced his comments on Ted’s Sweet Shop, 'Well now you’re talking about the ‘real’ Lake County.'

Panel 12: The Picture Brides

The late 1920s and the early 1930s were the eras of the Picture Bride. This was the time when the majority of Greek immigrant women came to the United States to marry. The migration of young men to the United States had resulted in an unprecedented lack of marriageable men for an entire generation of women. Historical events of the day only added to the overall absence of

men in the countryside. The Balkan Wars, World War I, and numerous natural disasters such as earthquakes and plagues created such a state of instability and economic hardship that marriage in America seemed, for many young women, the only reasonable option.

Whatever the hardships of everyday life in the rural countryside, few Greek maidens willingly wanted to immigrate. Brothers working in Illinois were more than willing to provide a handsome dowry but finding a suitable groom in the village of equal social and economic standing became increasingly problematic. The exchange of letters between various families in Greece and immigrants in America soon proved a viable means to overcome the lack of suitable grooms. In this growing correspondence, photographs would “just happen” to include, of say, a young Greek standing in front of his candy store on Halsted Street, or a portrait of a young maiden from a rural village. Sometimes these photographs initiated a highly formal exchange of letters between an unwed Greek immigrant in Illinois and a young Greek woman’s family in the rural countryside.

After an appropriate passage of time, if all parties agreed then legal dowry contracts, called prikes, were drawn up. The formalities involved in such traditional arrangements often created a very complicated series of exchanges. Very often brothers of the young maiden, from let us say Chicago, would send a sizable amount of money to relatives in their home village to fulfill their part of the marriage contract. This money would then be sent to the groom’s relatives in Alton, Illinois who were acting on his behalf in these formal exchanges.

Lest anyone think that this was simply a matter of “buying a husband” the groom was very often required to produce documents. Elaborate legal documents drawn up by officials at the Greek Consulate’s offices in Chicago were more frequently required than is discussed today. Testimonies from local parish priests concerning an individual’s character and bank documents showing total net worth and/or clear title on the property were commonly requested by the bride’s family.

Even after all these careful negotiations, the village women were fearful of the long voyage to an unknown land and a groom they had never even met. Many stories were whispered down by the village fountain where the young maidens gathered every day. Grim accounts of women left at the pier or train station because they were not as beautiful as their pictures made them seem to be.

Panel 13 Spring of 1922: Tasia Comes to Illinois

No single individual’s story could possibly represent all the Greek women who emigrated to Illinois during the 1920s and 1930s. Still, one woman’s story can illustrate some of the complexities in migration that all women experienced in one form or another. During the early Spring of 1922 Anastacia (Tasia) Rapanos left the rural village of Planaterou in the district of Kalavryta in the northern Peloponnesus for Chicago, Illinois.

Tasia was only able to leave because her brothers had started her emigration paperwork before the quota system imposed by the McCarran-Walter Act. This new legislation blocked her father Nikolaos from accompanying her. Although Nikolaos had made at least three trips from 1907 to 1919 to Chicago for extended periods of work he had never become an American citizen. Consequently, since he had not begun the process of seeking a visa before the McCarran-Walter Act restricted the terms of emigration, Nickolaos could not secure the necessary visa papers.

As far as the United States Emigration officials were concerned Tasia Rapanos was traveling alone. This created a problem. Rural Greek notions of propriety would simply not allow for an unmarried woman to travel alone. So, Nikolaos Rapanos made arrangements with a fellow villager, old friend, and distant cousin Sotiri Komberos to escort Tasia.

Tasia joined a group already consisting of four people: Sotiri Komberos, his young wife Demetra, their six-month-old son Yiorgos, and George Kokalis, Demetra’s younger brother. So restrictive were the United States emigration laws that young Kokalis had to appear on Sotiri Komberos’ travel papers as his son by a previous marriage.

Tasia waited nervously in the port city of Patras to have all her papers processed. Even during her stay in Patras propriety dictated that she be accompanied by her younger sister Olga. Unexpected family responsibilities almost caused Tasia to miss her boat for America!

While Tasia and Olga waited for all the endless paperwork to be completed, Vasso, a third sister, came to bring them back to the village. Eleni, yet another of Tasia’s sisters, was having a protracted and difficult childbirth. By the time the three sisters arrived, Eleni and her newborn son had both died. Given the limited conditions in the mountain villages, the funerals took place the next day. Immediately afterward, Tasia, Olga, and Vasso raced back to Patras. Tasia arrived just in time for the final presentation of documents and the boarding.

Within three years of her arrival in Chicago, Tasia was married at Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church and had an elaborate wedding party at Pullman Hall.

Panel 14 The Picture Bride Song

Sometime in the 1920s and 1930s, a folk song was composed that described the dread of these young women. Commonly referred to as the ‘Picture Bride Song’ this song became so popular it was eventually recorded in Athens as a 78-rpm record with the title 'Mother Please Don’t Send Me to America.' But the record was never sold in Greece. This record was target marketed by Columbia Records exclusively for the Greeks living in America. The famous lyrics of this song are:

Don’t send me to America, Mama

I’ll wither and die there!

I don’t want dollars---how can I say it?

Only bread, onions, and the one I love!

I love someone in the village, Mama

A handsome youth, an only son

He’s kissed me in the ravines,

And embraced me under the olive trees.

Yiorgo, my love, I’m leaving you

And going far away.

Ksenithia (the foreign lands).

They take me like a lamb to be slaughtered!

And there, in my grief, they’ll bury me.

Exhibition Research Every person of Greek descent whose family or families came to live in Illinois is indebted to the ongoing research of two men: Andrew Thomas Kopan and Peter W. Dickson.

Professor Andrew T. Kopan has an international reputation for his lifetime of research and writing on the Greek communities of Illinois. Dr. Kopan is the unquestioned Dean of Greek American regional studies for the Midwest. All succeeding generations of scholars owe Dr. Kopan a special debt not only for the high example his continued publications have provided over the years but for his singular dedication to the preservation of archival materials related to the Greek experience in the United States of America.

Mention needs to be made of the specialized and extremely detailed research and writings of Peter W. Dickson. Working alone, Mr. Dickson has reconstructed and documented the life and career of Christos Tsakonas. Mr. Dickson’s continued research as well as his attention to the preservation of critically important documents related to the experiences of numerous Tsintzinians in America places him in the company of young scholars responsible for the resurgence now underway in modern Greek-American historical studies.

Steve Frangos conducted all the research involved with this project, selected all the photographs, and wrote all the accompanying texts. Mr. Frangos has made extensive use of the photographs and research of Dr. Kopan as well as the writings of Peter W. Dickson. As the viewer will quickly see, Mr. Frangos has most heavily relied upon the work of Dr. Kopan. Nevertheless, the use of those photographs and the interpretive labels that accompany them are those of Mr. Frangos. Any and all errors in fact or interpretation are, of course, Mr. Frangos’ sole responsibility.

While the Heartland of Hellenism is a self-contained and independent exhibition display, it is a preview of the research topics that will soon appear in the upcoming museum exhibition ’O Cosmos: The Private Lives and Public Celebrations of the Greeks in Illinois: 1886-1992.’ The O Cosmos exhibition is a Greek-American Community Services, Inc. project which is sponsored in part by an Illinois Humanities Council grant award."

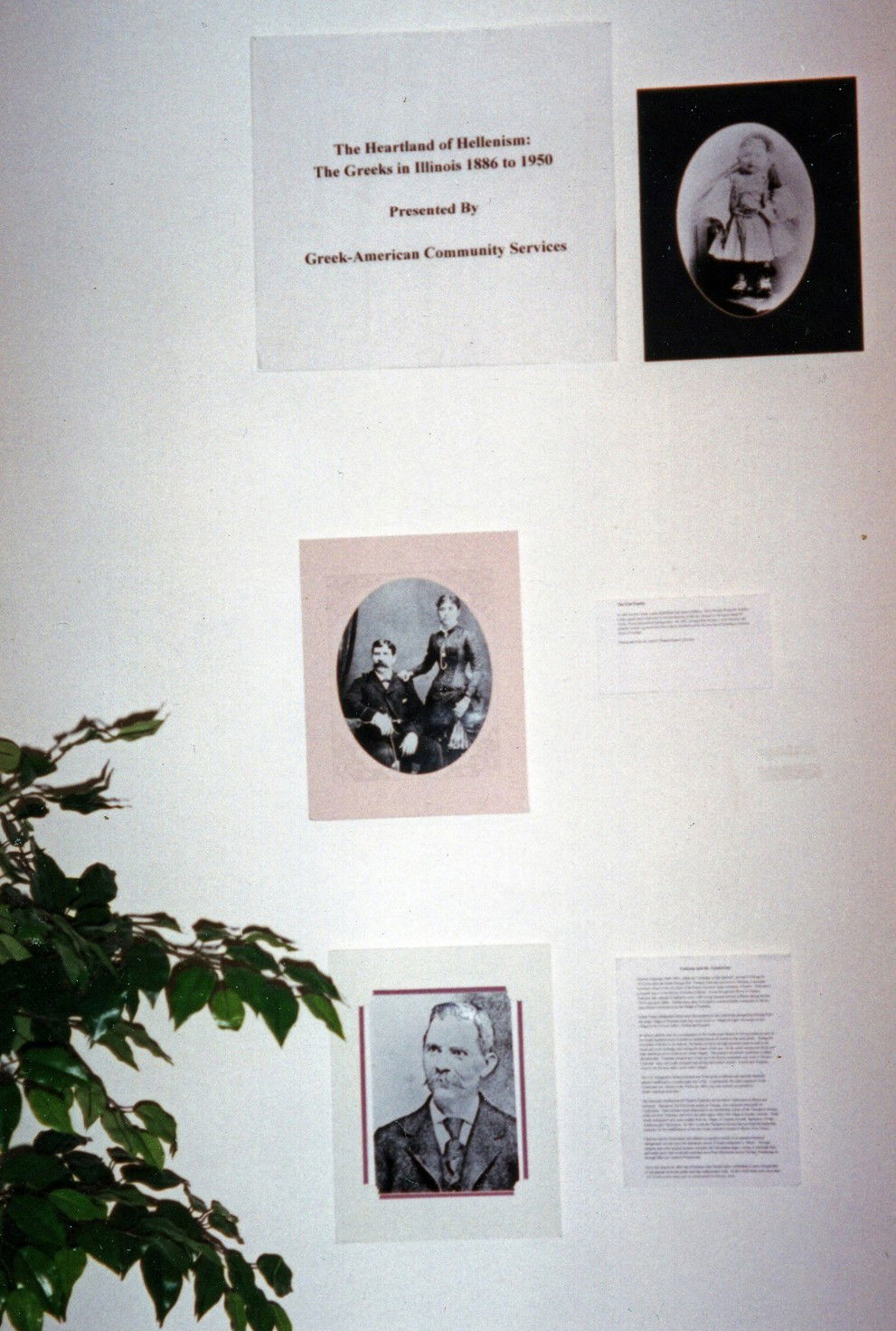

The first panel of the “Heartland of Hellenism: The Greeks in Illinois 1886-1950” exhibit. Top: unknown. Middle: Peter and Georgia Pooley. Bottom: Christos Tsakonas. Circa 1994. Photo by John Rassogianis. John Psiharis collection.

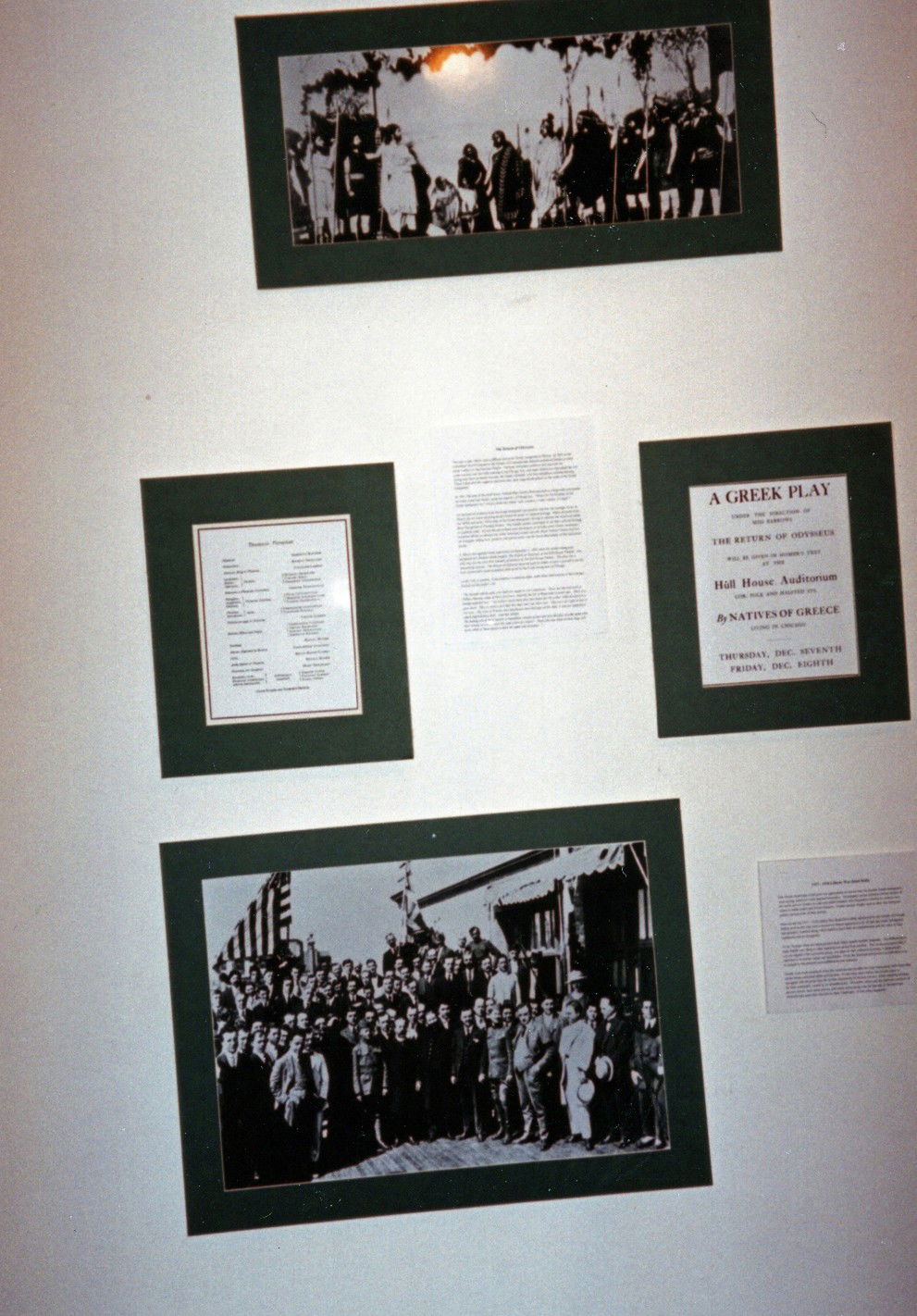

A panel from the “Heartland of Hellenism: Greeks in Illinois 1886-1950” exhibit. At top is a photo of the Return of Odysseus, play. In the middle is the playbill. On the bottom, the “Liberty War Bond” rally. Circa 1994. Photo by John Rassogianis. John Psiharis collection.

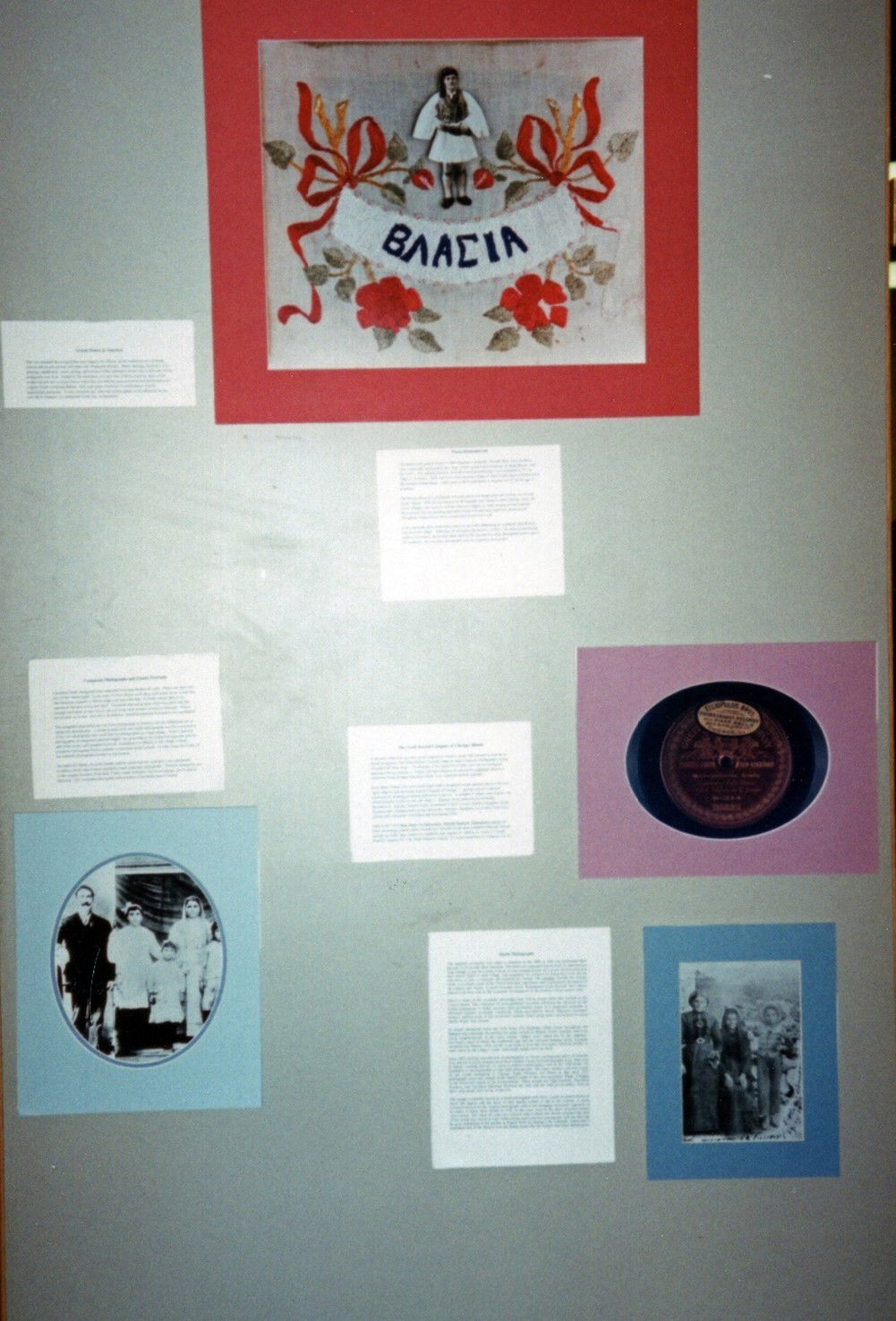

A panel from the “Heartland of Hellenism: Greeks in Illinois from 1886-1950” exhibit. Top: Needlework created by Zafiris Psychios. Middle right: A Greek Record Company of Chicago recording of the Elliopoulos Bros. Middle left: Christos Saramantis and his family in a 1903 photograph. Bottom: The family of Zafiris Psychios, circa 1917. Circa 1994. Photo by John Rassogianis. John Psiharis collection.

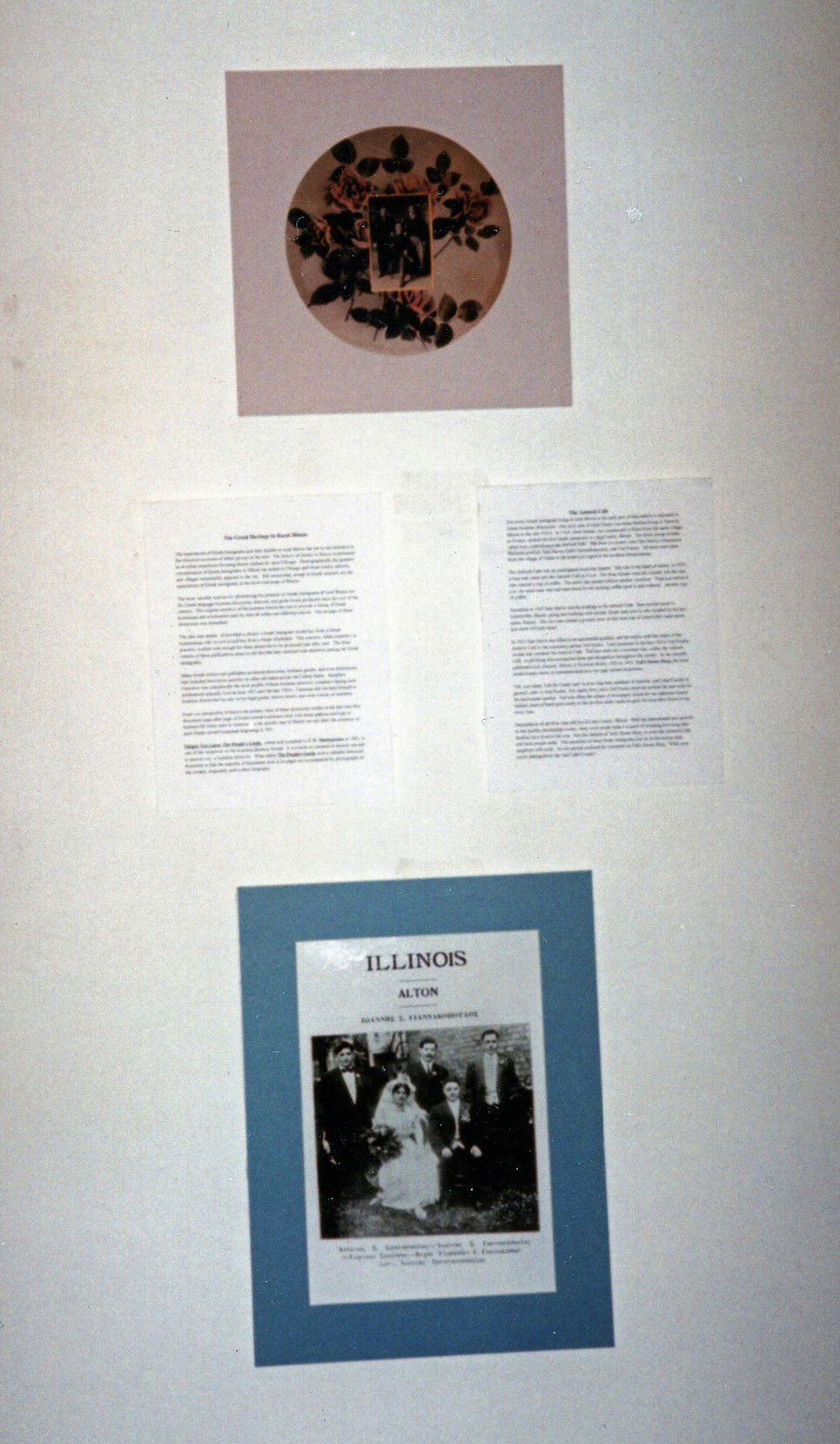

A panel from the “Heartland of Hellenism: Greeks in Illinois 1886-1950” exhibit. Top: An example of a composite photograph. Bottom: A wedding photo from a rural Illinois business directory. Circa 1994. Photo by John Rassogianis. John Psiharis collection.

(L): Photos from the Rassogianis family candy store. (R): A Chicago Sun Times article on Greeks at the Chicago World’s Fair. Circa 1994. Photos by John Rassogianis. John Psiharis collection.